Strathmore from Kinpurney

Landownership in Scotland and the myths that sustain it

This essay considers the state of landownership in Scotland and the many myths that help to perpetuate a system of such staggering inequality.

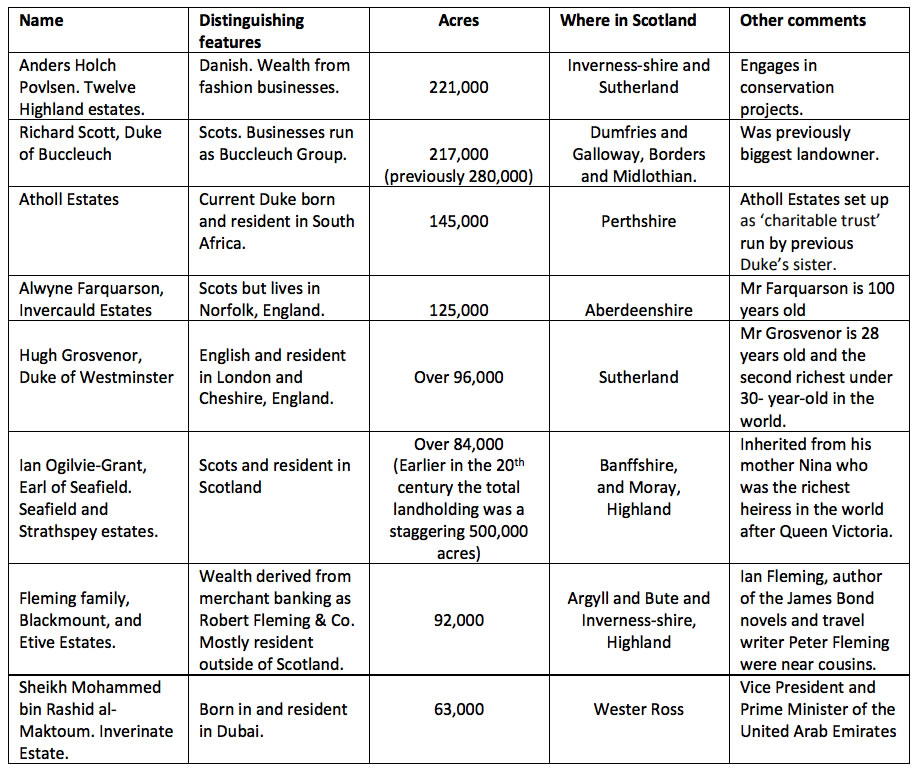

It is frequently argued that 432 landowners own half of Scotland. Whether or not this figure is currently completely accurate is hard to determine because land ownership information is often deliberately obscured and usually obfuscated.1Wightman, A. (2010 [2013]) The Poor Had No Lawyers: Who Owns Scotland (And How They Got It) 3rd Edn. Edinburgh: Birlinn. No matter whether the figure is precise, the overwhelming portion of Scotland is owned by a few hundred people and many of the largest landowners are from outside Scotland.2A more recent figure given by the Scottish Land Commission is that 1,125 owners own 70% of Scotland’s rural land (that figure includes public bodies such as Forestry and Land Scotland and the National Trust for Scotland). This massive imbalance has led academic and land reform campaigner Jim Hunter to claim that Scotland’s land ownership is

. . . the most concentrated, most inequitable, most unreformed and most undemocratic land ownership system in the entire developed world.3Hunter, J. (2013) Statement to the Herald in Wightman, A. (2013) The most concentrated, inequitable, and undemocratic land ownership in the entire developed world. Land Matters: the blog and website of Andy Wightman [Accessed 20 September 2020]

Some of the largest private landowners in Scotland are:

There are several hundred smaller estates ranging from 5,000 acres to 60,000 acres and owned by indigenous Scottish gentry, overseas buyers from as far afield as the US and Malaysia and spivs like Paul Dacre, ex editor of the Daily Mail, who fancy themselves as highland lairdies and who enjoy having a substantial chunk of land to lord it over.

Glen Affric, often considered the most beautiful glen in Scotland

Glen Affric, often considered the most beautiful glen in Scotland

Owned by Englishman, David Matthews, father of reality TV star Spencer Matthews and father-in-law of Pippa Middleton. Mr Matthews made his fortune in second hand car sales, owns an upmarket hotel in the Caribbean and has been investigated for rape and child sexual abuse.

Why?

I am often at a loss to understand how the intelligent, mostly educated and comparatively politicised population of Scotland allows a system of landownership, that is so obviously skewed in favour of a small, elitist and often absentee landlord class, to continue.

Perhaps we have been moulded into a nation of cap-doffers and forelock-tuggers by the ideologues working on behalf of the elites. But surely this would not sit well in a nation that produced William Wallace, Jenny Geddes, Rob Roy MacGregor, Rabbie Burns, Mary Somerville, John MacLean, Flora Drummond, Jimmy Reid and a host of other less well-known rebellious sorts.

I am more inclined to the notion that Scotland is brim-full of people who are very keen to see significant land reform but who are not yet well served by the political elites who represent them.

As part of a contribution to the struggle for meaningful and long-overdue land reform, I am aiming here to unpick some of the dominant myths that help to sustain concentrated land ownership in Scotland, in the hope that this unpicking will help others to counter the dominant narratives and take a more active part in dismantling this disabling system.

There are many myths about landownership which together sometimes bolster the sense of entitlement that allows big landowners to hold on to their land. The remainder of this essay is an effort to unravel some of those myths.

Myth Number 1: The Land or Estate – ‘has been in the family for generations’.

- By means of masculine primogeniture, it is argued that there has been a direct bloodline from father to son for generations, sometimes even a millennium. The phrase that was generally used to specify succession rights was ‘heirs male of his bodie lawfully begotten’ – which, in practice, meant sons of fathers born within wedlock. So, the law was specifically construed to both exclude women and those sons who were illegitimate and to establish that a blood line was required. It was also the norm for first born sons to inherit so that second and subsequent sons were expected to find other means of survival. Masculine primogeniture rules were sometimes broken in favour of women or non-blood relatives.

- Often this is only true (that the land has been in the hands of one family for generations) because, to keep an estate intact, fourth cousins twice removed (or something similar) are sought whenever there is a wee break in the direct line of male heirs. Sometimes blood relatives are bypassed in favour of in-laws or even outsiders as the imperative to maintain the estate is greater than familial bonds. Some inheritors are required to change their surnames in order to preserve the illusion that the estate has always been in the family and to keep the association with the symbolic family name.

- As is often pointed out, estates were often first acquired as royal or aristocratic grants for services rendered. That estates were dished out in dubious historic circumstances is no great argument for allowing them to remain intact and with relatives, close or distant, of the original receiver of benefits.

- It would be difficult to ‘prove’ that ‘heirs of his bodie’ whether male or female, were in fact what they are purported to be. Given the propensity of some aristocrats to engage in extra-marital affairs, it is more than likely that even some of the apparent blood descendants were biological imposters.

- Even where a direct blood line could be established, is this any way for a modern state to manage one of its primary resources – the land?

- And even in the cases where it is true – you’ve kind of had your turn – it is time to let others enjoy your good fortune.

Myth Number 2: Our pedigree is Scottish through and through. The estate is part of the backbone of Scottish history.

Most of the aristocracy can trace their ancestry back many generations because they were able to fund the lawyers, authors, clerks and painters who documented their lives.4This point is alluded to by Andy Wightman in the title of his book The Poor Had no Lawyers. By these means they can show that the estate, and sometimes the family name, have endured for centuries whether by legitimate or illegitimate means. While they are, for the most part, well assimilated now, it is worth acknowledging that most were immigrants and part of a conquering movement that significantly impacted on Scottish life in the medieval period.

- The most extensive acts of medieval estate granting occurred in the aftermath of the Norman invasion of England in 1066. David 1st of Scotland had multiple familial connections with the Norman rulers and aristocracy, lived among them in England for several years as a youngster and was willingly beholden to Henry 1st of England, son of William the Conqueror. During his reign (1124-1153) and in the period following, feudal estates were established with the installation of immigrant knights of Norman, French and Anglo-French provenance. Families like the Sinclairs, Bruces, Ramsays and Lindsays were allotted chunks of Scotland.5Sinclair = Saint Clair, Bruce = de Brus, Ramsay = de Ramesie, Lindsay may derive from de Limesie in Normandy.

- In addition to the French origins for some of the old estate dynasties, we need to question the Scottish allegiance of many of the, apparently indigenous, estate owners. For example, many Scottish estate owners also have lands in England. The Dukes of Sutherland had estates in Staffordshire and like many others of their ilk, spent far more time buttering up the royal court in London than managing their land in Scotland. Some of the bigger estate owners send their sons to Eton and then the University of Oxford. Unlike most Scottish voters, their political allegiance is usually to the Conservative and Unionist party with its loyalty to Westminster and the political hub in the South East of England.

Dunrobin Castle

Dunrobin Castle

If ever a castle was miss-named it was this one. The castle was the home of the Dukes and Duchesses of Sutherland, most infamous for their leading roles in the highland clearances.

Myth Number 3: My family worked hard to make and maintain this estate.

- Did your family build the buildings? Did your family fence or dyke the land? Did your family shepherd the sheep or husband the cattle? Did your family till the soil and cultivate the produce? No. Thought not. The actual hard grinding work on the land was done by the labourers, peasants, and hands who were mostly short-changed in the payment they received. The surplus value that you extracted from their work is the basis of your continuing landholding.

- This line is often used by the wealthy and not just in the landed classes. Entrepreneurs are often to be found promoting the idea that they work a great deal harder than everyone else. Some do. But many don’t work any harder than miners did, than nurses, teachers, firefighters, social workers and the police do. It is insulting to the millions of unsung workers who work extremely hard, and often in very challenging situations to have prosperous entrepreneurs virtue signalling about the very hard work they do. The implication is that they deserve their wealth due to their hard work and yet this does not translate into wealth for their hardworking underlings.

Myth Number 4: I have sacrificed everything for Downton (or my estate/farm etc)

This line is used in both the show and the trailer for the popular series Downton Abbey – which rather supports the idea that it is emblematic of a message that is being pushed. The series presents the stories of the upstairs family and their downstairs servants in the early part of the twentieth century.6Downton Abbey. Acclaimed television drama series broadcast on ITV in the UK between 2010 and 2015. A film under the same title and that continued the story was released in 2019. Created and written by Julian Fellowes. The show is set on an English estate although trips to relatives on their Scottish estate were included in the narrative. I am taking the liberty of using this media production as an example because it represents the myth so publicly. However, there is plenty of evidence that the myth is alive and well among Scottish landowners. Both upstairs and downstairs have their fair share of cads and heroes but the general ethos is of each knowing their place and getting on with their allotted duties: opening fetes and deciding on the fate of the land, and sometimes the country for those upstairs; scrubbing pans, baking pies, dusting bookshelves, personal grooming of their betters and generally kowtowing for those downstairs. I loved it – all those ball gowns and family intrigues – it was great television. Monarch of the Glen was a smaller scale and parochial Scottish version (with better views) of the same kind of programme.7Monarch of the Glen. Popular Scottish television drama series broadcast on BBC 1 between 2000 and 2005. It is set on a highland estate and is more comedic than Downton Abbey. The MacDonalds of Glenbogle are rather more down at heel than the occupants of Downton Abbey. Created by Michael Chaplin and based loosely on the highland novels (1941-1954) of Compton Mackenzie.

What sacrifices have the wealthy made? They have had the worry of working out how to sustain the estate and pay their workforce. Another way of saying this is to point out that they have enjoyed the power to control their environment and everyone in it. What many landowners seem not to grasp is the extent to which, not having control over your work, your home or your income is considerably more stressful when you have no control than when you do. If Downton went under, his Lordship would:

- probably have been able to secrete away enough to see him through,

- be able to call on his wealthy pals to see him right, till he got back on his feet and

- be able to fall back on his public school education, his military pals or connections in the city to sort himself out.

No such options for the downstairs lot who would have to go, cap in hand, to another bunch of rich people to beg for the privilege of sacrificing their own lives to help their employers live their lives.

Myth Number 5: The land is no use for anything else.

This is an argument extensively made about the Highlands of Scotland – basically that portion of Scotland above the Highland Boundary line which stretches roughly from the Clyde estuary to Stonehaven.8It is a geological boundary or fault line that separates the Dalradian rocks of the highlands from the Devonian terrain of Scotland’s mid-section. It can be traced as far as Clare Island on the Atlantic coast of Ireland. It is visually obvious in terms of the changes in landscape at many locations along its length, with, generally, mountains and moorland to the north and lower lying plains and valleys to the south. There are exceptions – Aberdeenshire and Moray, for example, contain exceptionally good farmland, Galloway and Roxburgh contain quite barren hills and moorland.

Let’s focus on the many vast lands of Argyll, Inverness, Ross, Sutherland, Caithness and the Hebrides for the moment. At one time population density was much greater in these areas – parts of which are now frequently described as ‘inhospitable’. In this relatively short piece of work it is not possible to go into the detail here, but it is possible to note the following:

- This land was forcibly cleared of people during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, mostly to make way for sheep farming. A whole way of life was significantly destroyed. The history of the Clearances is disputed territory but even those who lament how it has been mythologised into unmitigated oppression agree that most people were coerced off the land and, in some instances, violence was used to coerce them.

- Much of that land continues to be owned by large estates which are run as private fiefdoms and devote much of their use to what are politely called country sports. This includes deerstalking (and shooting), grouse, pheasant and hare shooting and fishing. Some also engage in some degree of (government and EU subsidised) agriculture and (government and EU subsidised) forestry operations and latterly some have branched into (government and EU subsidised) energy projects, fish farming and conservation efforts.

- The argument is regularly made that the land is of no use for anything other than providing sport for international and corporate wealth clients. In this respect Scotland sometimes resembles Batista’s Cuba in the nineteen-forties and -fifties as a playground for the wealthy – and that presaged the Cuban revolution.

- Could the land be used in other ways? Undoubtedly. Would the landscape suffer if more people lived in it – of course not – in fact it would redress the awful dearth of people caused by the clearances. I am as susceptible as the next person to the joys of walking in an empty glen or looking out onto an expanse of barren moorland9Few places are as evocative, and occasionally downright scary, as Rannoch moor. I know, I once walked across it in sideways sleet and my fluorescent green, plastic rain cagoule ended up as confetti (with apologies to the environment – it was a while ago). but Scotland has an abundance of relatively empty space, some of which could easily be deployed for homes and businesses without too much loss for those of us who want to enjoy the great outdoors.

- The scope for Scotland to utterly reconsider how land is accessed, managed, distributed, used and enjoyed is enormous. Some notable gains have been made – such as Right to Roam and Community buyouts – but so much more needs to be done.10The ‘Right to Roam’ is the common name for that portion of The Land Reform (Scotland) Act of 2003 which gives everyone rights of access to land and inland water throughout Scotland so long as they act responsibly. Community buyouts refers to the ‘Community right to buy’ encapsulated in the same 2003 Act and extended and updated since. It gives local communities a pre-emptive right to acquire land and has resulted in increasing numbers of acquisitions of property by local communities

- As far as specific suggestions go – with good internet connections (and I am aware of the difficulties caused by poor internet connection and the related difficulties of providing good networks in remote areas) the scope for repopulating the Highlands is enormous. With good will and increased infrastructure, a thriving, engaged and employed workforce in the Highlands is a possibility – but not if we leave the current situation as it is. There are myriad possibilities for small business development and innovative approaches to co-operative living and new community-based ventures. Help with infrastructure needs to occur as does freeing up land-based resources, allowing people to take control of their local environment and ensure it is run sustainably and in the interests of everyone or at least the majority.

- Innovations in agriculture, such as polytunnels, need to be pursued to allow more people to live off the land and to help those who want to, to set up and run smallholdings or crofts or their modern equivalents.

Caithness View

Caithness View

Myth Number 6: Most townies and indeed, most people not born to this lifestyle, wouldn’t know how to work it.

This is a favourite in agriculture.

This was, until recently, commonly heard in the backwoods of Scotland. If you weren’t born and raised to farming, you probably wouldn’t be able to survive your first couple of years in it. The folk wisdom of agriculture was passed down in families and communities and those who were not party to the lifestyle wouldn’t know one end of a bullock from the other.

The story has shifted in recent years due to a shortage of young people wanting to continue to farm. Efforts have gone into trying to encourage young people to take up farming and a wide range of courses in agriculture and related subjects, once the exclusive province of farmers’ sons, is now on offer to a wide range of students. This is supplemented by numerous documentary and reality tv shows aimed at showing farming to be a sexy alternative career for uncertain youngsters. The change is also a consequence of the increasing technological complexity of much modern farming. For arable farmers to cope well with changes in insecticides and fertilisers (organic or non-organic) and the appropriate balances between these, a knowledge of chemistry is necessary to an extent that was not previously known. Tractors are now computerised so that anyone unable or unwilling to respond to digitalisation would exclude themselves from that kind of work. Accounts, tax, subsidies, trainings, hygiene, safety, quality monitoring and registration of animals must all be done online, and these very often fall to the wives and daughters of farmers who themselves, may or may not, be up to speed with this kind of activity. This is, incidentally, one of the ways that women have wrested some control in farming. They are very often the only one who really knows what is going in the farm accounts and this has sometimes been a source of power for farm-based women.

- One thing that is important to keep in mind here is how close most Scottish townies are to their agricultural and rural heritage. It’s a bit like religious history – 500 hundred years ago we were all Catholics. A similar argument applies in agriculture. Two hundred years ago we were all teuchters.11I was reminded by a highland friend that ‘teuchter’, a lowland Scots word, was used to insult highlanders. Where I grew up in Perthshire it was somewhat derogatory and meant rustic or rural dweller – akin to the English ‘country bumpkin’ or American ‘hillbilly’. It tended to mean ‘You are more country than I.’ I think it is time for us to reclaim this evocative word and be proud of our teuchter heritage. Most of Scotland’s population lived on the land until the twentieth century. You don’t have to go far in a conversation with town or city based people to unearth stories of grandads, uncles, parents or old neighbours who were country based but who were propelled to seek alternatives to poverty, poor or nonexistent housing, unemployment and the like and to move their base of operations to urban areas. Even many whose direct links to the land were much further back, still had ties to the countryside by way of extended holidays. Vast numbers of Glaswegians and Dundonians spent many weeks picking berries in the summer and gathering tatties in the autumn and this didn’t really change significantly till the 1990s – barely a generation back.

- Of course, being reared in an agricultural environment could be argued to be an advantage in terms of knowledge and experience when it comes to deciding who should work on the land. However, it could equally be viewed as an obstacle in a scientific age when outmoded techniques and surpassed knowledge might hinder innovation and development. Knowledge can be taught, experience can be gained and a passion for agricultural work is not something that is inborn and, like all passions, subject to vast variation. Not every farmer’s son wants to farm though incentives are high and especially for those born into large or lucrative concerns. Not everyone raised in the town wants to stay in the town. There must be room for movement and especially in a world in which jobs are not for life and careers include significant detours and changes. Some of the most innovative and enthusiastic farmers today are the young people and mid-lifers who have gone into farming from very different backgrounds.

Myth Number 7: The Clearances were a marvellous thing – they gave many people opportunities in the US and Canada etc. that they would otherwise not have had!!!

This is an argument purveyed by apologists for the Clearances. It is partially propped up by some of the diaspora as it is a way of telling a happy story about the Clearances and a happy story about belonging, with gusto, to a country such as the USA. This is true, notwithstanding that members of the diaspora, and especially the diaspora in Canada, are sometimes the most fervent lamenters of the tragedy of the Clearances. It has also, in recent years, been given a fresh injection of support by the 2006 publication of a book by Michael Fry that was described as a ‘Clearances denial book’ and which suggested both that the clearances were exaggerated and that most evictees had wanted to move for self-improvement purposes.12Fry, M. (2006) Wild Scots: Four Hundred Years of Highland History London: John Murray. Labour MP Brian Wilson called the book ‘A Clearances denial book’ and called Fry ‘a buffoon’. N.B. Most extant studies have focussed on the highland clearances. Tom Devine and others have argued, convincingly, in more recent years that significant clearances occurred in lowland Scotland. See Aitchison, P and Cassell, A. (2003) The Lowland Clearances: Scotland’s Silent Revolution Birlinn: Edinburgh, Devine, T. (2018) The Scottish Clearances: A History of the Dispossessed, 1600-1900 London: Allen Lane.

There were many people who went to America, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and other colonial destinations who subsequently made good lives for themselves. However, to frame this as a great opportunity for them is to gloss over many fundamental problems:

- Most arrived in their colonial destination with nothing and had to strive in very difficult conditions to survive. Others, of course, perished on the very dangerous journey or after arrival;

- Most were forcibly removed from environments they had been in as far back as memory could attest. Most were pushed out against their will and some at the point of violence;

- The most significant problem with this statement is that it fails to acknowledge that at no point in the proceedings that led to their migrations were people consulted about what their desires might be. It was taken for granted that the rich and powerful who were making decisions in their own economic interests had every right to remove people off ‘their’ land and then on to boats and on into colonial backwaters, because those people had no voice, no democratic rights and no human rights. Some people have been known to argue that as ignorant and fearful peasants they needed a kick up the backside and wouldn’t have had the wit or gumption to propel themselves forward in ways that might have been in their best interests. The arrogance of such a view hardly bears a response.

The remains of homesteads on the West coast of Lewis. The ruins of homes like this can be found all over rural Scotland.

The remains of homesteads on the West coast of Lewis. The ruins of homes like this can be found all over rural Scotland.

Myth Number 8: We love the land more than others do.

This sentiment is expressed regularly in a variety of forms. We have loved and nurtured this estate for generations. No-one else has such close ties to this property as we do. Outsiders wouldn’t understand the deep bonds that link us to this place.

- No-one would surely doubt that people who have been closely associated with a place would not have strong emotions about it. But would not that same argument apply to all the people who are associated with the place – the labourers who built it, the peasants who carved out a life there, the herds who looked after the animals, the ploughmen and women who dug and cultivated the land and the foresters who managed the woods.

- However, if your association with the place has been particularly beneficial for your family as a source of profit and prestige then maybe you have a more substantial interest in the place – and could claim therefore to love it that bit more! It takes a certain kind of elitist mentality to imagine that this is something acceptable for your family while others do not enjoy such privilege – indeed, while the underpaid work of others is often the source of your good fortune.

- There is also the idea of ‘love’ that is employed here. This is not the love of the artisan for the material earth that they work with or of the shepherd who tramps the hills every day. While this ‘love’ might be imbued with pastoral sentiments evoked from literature it is also often the ‘love’ of absentee landlords who ‘own’ a property but who spend only short periods there because of their other commitments to the House, the city or the Season, leaving the real work on estates to managers, factors, keepers and household staff.

Myth Number 9: We are just stewarding the land for future generations.

This is heard more recently – and probably in direct response to the promotional efforts of conservationists, environmentalists and land reformers. This wee narrative has surfaced in recent years and is certainly not accepted widely. There are still plenty of landowners who talk vehemently in terms of MY LAND – and MY RIGHTS TO DO WHATEVER I LIKE ON MY LAND. However, the more politically attuned among the landowner class have begun to, at least publicly, ape the sentiments of conservationists and/or land reformers in proclaiming that ‘we know that we are just stewards of this land for the next generation.’ What they fail to acknowledge is that when they talk about the next generation, they are talking about their own children not yours or mine.

- If they are ‘just stewarding’ perhaps they could show via legal documentation how they will be returning their land holdings to the common pot for all to enjoy and not just their own descendants.

- If they are ‘just stewarding’ then they need to be much more open to community involvement in their stewarding policies because policies that are designed to further their own business interests may not be aligned with the future interests of the communities surrounding them.

- Watch out also for landowners who are ‘just custodians’, ‘just caretakers’, ‘just guardians’ and ‘just protectors’ of the land but rarely actually ‘just’.

Myth Number 10: It’s a charitable trust/community trust/heritage trust – we don’t own it anymore.

The famous Bealach na Ba (pass of the cattle) on Applecross.

The famous Bealach na Ba (pass of the cattle) on Applecross.

Hmm. This is an interesting one and one that is being employed to extensive effect by landowners who are either cash-strapped or a bit under siege but who want a way of holding onto ‘their’ heritage.

- See for example the Wills family in Applecross. Applecross is a huge peninsula not just a shoreside village – which is often the impression people seem to have. The Wills family (of WD and HO Wills, Bristol tobacco importers) purchased the Applecross estate (70,000 acres) in 1929. By 1975 they wanted to divest themselves of the estate because of concerns about Capital Transfer taxes but at the same time maintain control of it. They set up the Applecross Trust which doesn’t allow people in the community to join, which controls much that operates on the peninsula and which, until recently, allowed the family to hold on to Applecross House on a peppercorn rent and to retain fishing rights for a princely £10 per annum. Richard Wills, whose residence was in the South of England, was chair of the Applecross trust for over twenty years until 2017.

- The massive Atholl Estate (approximately 145,000 acres) in Perthshire is now run and controlled by a charitable trust headed up by the sister of the last Duke. The current duke lives in South Africa.

- Brodie Castle in Morayshire was the seat of the Brodies of Brodie (from 1160 when it was reputedly given to the family by King Malcolm IV). By the mid twentieth century the maintenance of the castle was sucking more finance than the laird could find, and he would have had to sell off the furniture to pay the bills. In 1978 Ninian Brodie of Brodie handed over the castle and estate to the National Trust with a deal that paid him £130,000 (around £800,000 today) and a flat in the castle for life. Some of his descendants were notably displeased. This kind of deal was set up with many other castles and landed properties.

Many of the most substantial estates are ‘owned’ by ‘trusts’ of one sort or another. This is a way of obscuring ownership, hiding assets, taking advantage of legal loopholes, locating ‘ownership’ in overseas territories, deriving benefits from spurious charitable status and almost always about tax avoidance.

Myth number 11: We are entrepreneurs using above average ingenuity and extraordinary panache to set up and run our businesses from nothing more than our own brilliance.

While there are examples of Scots demonstrating above average inventiveness and savviness to develop, build and sustain their businesses it is worth looking more closely at some of the opportunities that landowners can access that are not so available to others.13There are plenty of examples of Scots, whether admirable or not, who really did start businesses from near nothing – for example, William Lithgow the shipbuilder, Robert Fleming, the Dundee clerk who started an international investment bank, Brian Souter and his sister Ann Gloag from Perth who set up Stagecoach and, of course, the example most often cited, Andrew Carnegie who made his fortune in American steel.

- In the first instance, having access to land provides an unbelievable resource from which to develop rural businesses. That’s one of the reasons why I am not very sympathetic to the idea that holding land is such a great burden (See Myth number 15 below). Try setting up and developing a rural business without any land – it is much more difficult.

- Access to funding. Business loans and mortgages are relatively easy with land.

- Landowners have easier access to subsidies – charitable, local government, Scottish government, UK government and EU. One example is the setting up of very lucrative renewable energy businesses. These could and should be developed by and for the benefit of local communities, but they are often set up by private landowners who can claim substantial public funding and then rake in their subsidised profits. Jobs for the boys.

- If everyone had access to the advantages that landowners have in order to set up businesses, many more bright, innovative entrepreneurs would have real opportunities to set up and run their businesses.

- Given the significant advantages available to landowners, their businesses ought to have a much higher success rate than those of less well-placed entrepreneurs.

Myth number 12: Our Ancestors were spectacularly good entrepreneurs and that’s how we got our landholding.

Caricatures of black people on the walls of Dunrobin Castle. Black people appear often in the eighteenth and nineteenth century artworks in Scotland's big houses. Usually they are un-named, sometimes they are caricatured as here and more often than not they are linked to the slave trade.

Caricatures of black people on the walls of Dunrobin Castle. Black people appear often in the eighteenth and nineteenth century artworks in Scotland's big houses. Usually they are un-named, sometimes they are caricatured as here and more often than not they are linked to the slave trade.

While this is true in some instances (See footnote 12). It is also true that there are few Scottish landholdings of any significant size that did not benefit from slavery or from other highly questionable forms of colonial exploitation. The Atlantic slave trade is directly implicated in the sustenance and setting up of many landed estates, including those forfeited by Jacobites but reclaimed with sugar and tobacco plantation profits. The colonial pillaging of India, Chinese opium, Asian rubber and African gold and diamonds were also often bankrolling estates in Scotland.

Myth number 13: People love their social superiors and love to defer to them

I mentioned cap-doffing and forelock tugging earlier. There does appear to be some strand of deference that some Scots subscribe to. I had an aunt who talked about members of her local gentry as if they were a) a definite cut above the norm and b) personal friends on first name terms (although she only actually knew them in situations in which she deferred to them and/or worked for them). My mother, who leaned towards a socialistic viewpoint, would talk about the aristocrats who overlooked her childhood with a generous-hearted interest. She was fascinated by the minutiae of their privileged and gilded existence and remained deeply sympathetic to their personal tragedies and ultimate fall from grace.

A staple character of many ‘big house’ dramas is the deferential lackey who sycophantically panders to his lord’s every wish and who appears to live his life in the shadow of and for his master. This can take the form of comedy where we laugh at the idiot for his unrequited condescension, or tragedy where we look with pity on the lost life of the brown-nose.14An example of the latter would be James Stevens the butler in Kazuo Ishiguro’s 1989 Booker prize-winning novel The Remains of the Day, notably played by Anthony Hopkins in the acclaimed Merchant/Ivory film of the same name (1993).

The Airlie monument north of Kirriemuir in Angus, honours the ninth Earl of Airlie who was killed in June 1900 fighting in the second Anglo-Boer war to maintain British imperial supremacy in Southern Africa. The Earl was one of over 30,000 soldiers to die in this war, more than two thirds of whom were on the British side, and over a hundred thousand others were wounded, invalided or missing.15The Earl was killed leading 60 men of his then regiment, the 12th Lancers, to try to take Boer guns at the battle of Diamond Hill (or Donkerhoek). This battle took place on the 11th and 12th of June and resulted in around 60 killed and 100 wounded. Previously he had taken part in colonial wars in Afghanistan (1878-9) and Sudan (1884-5). It was during the second AngloBoer war that British forces employed ‘scorched earth’ policies to starve out local populations followed by the development of concentration camps, where, notoriously, over 26 thousand Boer women and children died.

This monument is one of many that tries to sustain a myth about the lovability of local overlords. The memorial plaque, begins by stating that: ‘In the year 1901 under the sense of a great loss and a feeling of sorrow, his own people, his countrymen, and his friends, united in raising this monument to perpetuate the revered memory of . . . [the Earl].’ Further down, and among other things, it mentions that he was ‘Full of Christian and knightly virtues. . .’, and a ‘beneficent landlord.’ The ceremonials to herald the building of the monument were overseen by his friends in the local Masonic Lodges.16I was told recently that the owner of Airlie estates was considering applying for charitable status in order to gain funding to maintain and upgrade the monument – which is a bit frayed at the edges. If true, this would be yet another example of the landed seeking benefits to improve their property

This is one among many instances of a story of great love and reverence for a local laird that is scraped onto stone or carved into marble for all to see, read and imbibe. Here are two other examples:

The famous and very controversial statue of the Duke of Sutherland looks down from Beinn Bhraggie onto Golspie. Locals refer to it/him as ‘The Manny’. There are regular acts of subversive graffiti and, periodically, campaigns to tear it down. Many locals tolerate the statue as a tourist attraction while, usually, remaining contemptuous of the man himself.

The Panmure Testimonial is a 32-metre phallic monument commemorating an act of putative generosity on the part of William Maule, 2nd Earl of Panmure.17The de Maule’s were another of the 11th century Norman French cohort. Carnoustie has, since 1992, been twinned with Maule, a small town to the north west of Paris, France from whence came the original de Maule family. He owned the Panmure estate near Carnoustie. When, in 1826, drought conditions meant harvests failed and food was in short supply, Maule suspended the collection of rents from ‘his’ tenant farmers. The monument was subsequently erected in 1839 and paid for by the tenants. Panmure house, an eighteenth and nineteenth century pile was once one of the finest houses in Scotland. It, and the castle that preceded it, have gone, but the monument remains at the end of a magnificent avenue within the decaying and neglected woodland estate (which is now broken up).

There are many other examples like this. These statues are different from the memorials to the ordinary soldiers who gave their lives in the first and second world wars. These statues honour one wealthy man who lorded it over a local area and they demand that, even in death, these men are to be placed, both socially and physically, above others.

We are often told that politicians, and especially those who are regarded as questionable by the traditional establishment, engage in purveying ideologies. These statues are permanent sites of ideology. The ideological message is that our economic and political superiors are to be elevated and celebrated and we are invited to, indeed cajoled into, accepting that it is normal and right for us to bow to their more important status. We are told that we do (and must) ‘love’ our social betters and yet they are not always so loving in return.

Myth Number 14: To farm land, you need to own it.

No-one has the indecency to say this out loud anymore, but it is nevertheless a prevalent myth. It is one of the reasons that tenant farmers are often viewed as second-class. This abiding notion is widely held in the agricultural world, and especially by those who are known as ‘gentleman-farmers’. The underlying idea is akin to the related British idea that homeowners are better than tenants because they will have a vested interest in the longterm upkeep of a property.18Compare with rented accommodation in continental Europe. Likewise, it is thought that because the land itself is invested in, then farm owners will look after a property better than tenant farmers. There is certainly a logic to this – the long -term future of land is likely to be of more concern to an owner than a tenant. However, even this apparent truism relies on mythology:

- There is only anecdotal evidence for any of this.

- Tenant farmers may maintain and improve property more than an owner precisely because they want to ensure their tenancy will continue.

- One person’s improvement might be another’s disaster.

The crucial thing to consider here is who would do farming if they did not own the land? Farmers should be farming because they like farming, are good at it and qualified to do it, and not because they have been left land to make a living from. It would be interesting to see how many of the enthusiastic farmers we have today would remain enthusiastic when their enthusiasm is solely for farming and not at all for land-owning.

Myth Number 15: It is all a terrible burden. The efforts we must make to try to keep the estate going are shocking. We have had to make unbelievable sacrifices for our estate.

This is a particularly irritating myth. This is ungracious owners decrying the great encumbrance of an estate when so many – so, so many – are denied such a luxury. It really sticks in the throats of the under-privileged when the over-privileged bemoan their lot. I don’t want to dwell on the sacrifice side of things as it has already been dealt with above but rather to question the terrible burden notion.

- If it really is such a terrible burden – put it down and let the rest of us join collectively to carry it.

- If you feel the terrible weight of duty and history to maintain a parcel of land that your family has held for too long, let it go. We, and history, will not judge you for returning land to the community. We, and history, will probably judge you for clinging on too long.

- If the window taxes and the capital gains and the inheritance dues, not to mention the costs of restoring leaky roofs are too much of a stress and worry for you, and we can sympathise that they might be – be so good as to recognise that this is because you no longer have access to a fourteenth century workforce who are willing to live off scraps while slaving for you – and that, for the vast majority of people, this is a good thing.

Myth Number 16: We are providing work for the local population – they would be the losers if we moved on.

Cawdor Castle

Cawdor Castle

Cawdor Castle is a popular tourist attraction near Nairn. It has been the subject of inheritance disputes in recent years.

This myth is promulgated far more widely than just in relation to land-owning, but it is worth focussing on it because it is used, quite cynically, to justify otherwise ridiculous circumstances.

Let’s start with:

- Why are you providing work for the local population? Is it because you have a paternal interest in their wellbeing? You might. You might be one of those paternalistic types who feel they have a duty of care to the poor folks in the neighbourhood. But perhaps, also, you need the people to work for you just as much, if not more so, than they need to work for you.

- Why are you the one providing work? Is it because you and your family, for generations, have lain claim to the valuable resources in the immediate area? The coal and the slate and the fields and the watercourses and the woods all belong to you and if anyone wants to engage in some creative or developmental work, they must apply to you to use these resources. If they even want to gather firewood from your forest, they need to ask your permission or pay a fee. If they want to forage for food for the pot, they will find themselves on the wrong side of the law which you and your peers have made for the protection of ‘your’ property.

- And – this argument – that you are providing work for locals (the sub-text being that you should receive public support and maybe even financial subsidies to prop up ‘your’ business) – which is used ubiquitously whenever a firm is under some threat – could equally have been used for Belsen or Auschwitz-Birkenau and only vile Nazis would argue that they should have continued. Some things are even more important than local employment. A prior question as to the social value of an enterprise for all stakeholders needs to be addressed before the specific question of local employment is dealt with.

- The, sometimes stated, corollary of this argument; that these stupid peasants wouldn’t know how to organise themselves into a co-operative group to further their own development or that of their local community without the managerial guidance of their social betters, has been demonstrated to be a fallacy on many occasions.

Myth Number 17: Scotland is basically a tourist destination – high calibre of course but nevertheless a service economy for incomers to enjoy.

What is wonderful about Scotland is its majestic scenery, awesome space, wild and savage mountains, rugged moorland, beautiful lochs and glens, dens and straths. Tourism is great – but the needs and desires of tourists must be balanced with the needs and desires of residents. Parts of Skye, West coast areas like the Applecross peninsula and the North coast have seen increases in tourist traffic that are unsustainable in the medium term. At the same time, traditional inland resorts such as Strathpeffer have seen their tourism industry, upon which they were very reliant, suffer a significant drop as tourists are shepherded to new destinations – or worse, encouraged to speed round the coast and barely contribute to the local economy. There’s a lot of empty space in the Highlands (and in parts of the Borders and Dumfries and Galloway) so there’s plenty of room for more residents and visitors but infrastructure needs to be developed to cope with influxes.

- We need to have country-wide debates about short, medium, and long-term objectives in tourism. Do we want to be one of those sad places where the population is overwhelmingly reduced to roles servicing the needs of visitors? Where the only important skill is bowing and scraping and making visitors feel they are being pampered by customer experience specialists. There is plenty of scope in Scotland for upgrading customer relations training. Nobody is having a good time when a customer tries to buy a snack from a reluctant café employee who would prefer to continue texting his or her pals. But a balance needs to be struck so that the whole country doesn’t find itself in hock to running a glorified theme park and where most of the population finds itself trying to earn the tourist dollar. Tourism has its place in Scotland’s economy, but it cannot be the economy.

- Scotland’s resident population are having a hard time finding homes for themselves. At the same time, villages, towns and cities in tourist hotspots have second homes that are rarely used, holiday houses that are let to visitors and flats and houses that are rented out through sites such as Airbnb. In the case of small or remote villages, local people cannot access homes because owners can command much higher rents from short-term visitors. Young people on Skye are being driven out because although they have jobs, they cannot find local accommodation. Businesses cannot hire staff because the staff have nowhere affordable to live. Villages become like ghost towns because the local population are priced out and second homes lie empty for months at a time. Communities are destroyed by these processes. In substantial city-centres like Edinburgh, residents and students compete in an inflated rental market with short-term Airbnb renters so that communities are ‘hollowed out’ while unscrupulous ‘landlords’ (sometimes sub-letters) make a short-term killing.19Bol, D. (2019) ‘Dozens of rogue Airbnb-style flats in Edinburgh hit with warning letters.’ The Scotsman 15th May 2019

- Scotland sells itself via images of mist, heather, empty glens, desolate moorland, loch and seascapes, snowy peaks and abandoned farmsteads – usually with a strategically placed piper, thistle or highland cow for added, if manufactured, ‘authenticity’. While most Scots have a well-developed love of their country and its awe-inspiring vistas, many will question whether quite so much of it needs to be given over to meeting the (partially manufactured) desires of tourists. A further debate needs to be had about whether empty straths like Kildonan, Carron or Tummel – wonderfully evocative for the returning diaspora – really need to continue to be empty – or if there is not real scope for Scottish people to pursue their dreams by re-building vibrant communities in such places.

Conclusion

The preceding myths help to support and sustain a mode of land distribution, ownership and management that has long had its day. These myths need to be deconstructed and shown for what they are – madey-up stories that allow a small group of people to take advantage of Scotland’s land resources while far too many of Scotland’s population have little or no purchase on the ground beneath their feet.

The impetus to land reform in Scotland has gained momentum in recent years. It needed to. For far too long, vested interests and feudal arrangements have held sway in Scotland’s rural areas. While outmoded seigneurs pat themselves on the back for belatedly starting a renewable energy project, turning a barn into a wedding venue, marketing meat from rare breeds or cold-pressed rapeseed oil, or turn their surplus cottages into holiday rentals, none of this helps to distribute land more widely. Land that was once handed out in parcels to buy the loyalty of what were essentially the gangmasters of their day needs to come back into more widespread ownership. The people of Scotland should ‘own’ Scotland and anyone who holds a landholding of more than a few acres, should be renting it from the nation and be required to manage it in the interests of the nation. Efforts to promote land value taxation would help steer us towards that eventuality. Those people who work and live on Scotland’s land – and that should ideally be anyone who would like to – have every right to be recognised as the real custodians of the land, for now and in perpetuity.

The Scottish government has begun some work to bring about land reform, but this is too little and too slow for most Scots. Much more action is needed to make meaningful change that completely undermines the small, and often absentee, oligarchy who currently own and control Scotland’s land and replaces them with ordinary Scots who, quite reasonably, want a wee stake in their own country and its future.

Notes

1 Wightman, A. (2010 [2013]) The Poor Had No Lawyers: Who Owns Scotland (And How They Got It) 3rd Edn. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

2 A more recent figure given by the Scottish Land Commission is that 1,125 owners own 70% of Scotland’s rural land (that figure includes public bodies such as Forestry and Land Scotland and the National Trust for Scotland).

3Hunter, J. (2013) Statement to the Herald in Wightman, A. (2013) The most concentrated, inequitable, and undemocratic land ownership in the entire developed world. Land Matters: the blog and website of Andy Wightman [Accessed 20 September 2020]

4 This point is alluded to by Andy Wightman in the title of his book The Poor Had no Lawyers.

5 Sinclair = Saint Clair, Bruce = de Brus, Ramsay = de Ramesie, Lindsay may derive from de Limesie in Normandy.

6 Downton Abbey. Acclaimed television drama series broadcast on ITV in the UK between 2010 and 2015. A film under the same title and that continued the story was released in 2019. Created and written by Julian Fellowes. The show is set on an English estate although trips to relatives on their Scottish estate were included in the narrative. I am taking the liberty of using this media production as an example because it represents the myth so publicly. However, there is plenty of evidence that the myth is alive and well among Scottish landowners.

7 Monarch of the Glen. Popular Scottish television drama series broadcast on BBC 1 between 2000 and 2005. It is set on a highland estate and is more comedic than Downton Abbey. The MacDonalds of Glenbogle are rather more down at heel than the occupants of Downton Abbey. Created by Michael Chaplin and based loosely on the highland novels (1941-1954) of Compton Mackenzie.

8 It is a geological boundary or fault line that separates the Dalradian rocks of the highlands from the Devonian terrain of Scotland’s mid-section. It can be traced as far as Clare Island on the Atlantic coast of Ireland. It is visually obvious in terms of the changes in landscape at many locations along its length, with, generally, mountains and moorland to the north and lower lying plains and valleys to the south.

9 Few places are as evocative, and occasionally downright scary, as Rannoch moor. I know, I once walked across it in sideways sleet and my fluorescent green, plastic rain cagoule ended up as confetti (with apologies to the environment – it was a while ago).

10The ‘Right to Roam’ is the common name for that portion of The Land Reform (Scotland) Act of 2003 which gives everyone rights of access to land and inland water throughout Scotland so long as they act responsibly. Community buyouts refers to the ‘Community right to buy’ encapsulated in the same 2003 Act and extended and updated since. It gives local communities a pre-emptive right to acquire land and has resulted in increasing numbers of acquisitions of property by local communities.

11 I was reminded by a highland friend that ‘teuchter’, a lowland Scots word, was used to insult highlanders. Where I grew up in Perthshire it was somewhat derogatory and meant rustic or rural dweller – akin to the English ‘country bumpkin’ or American ‘hillbilly’. It tended to mean ‘You are more country than I.’ I think it is time for us to reclaim this evocative word and be proud of our teuchter heritage.

12 Fry, M. (2006) Wild Scots: Four Hundred Years of Highland History London: John Murray. Labour MP Brian Wilson called the book ‘A Clearances denial book’ and called Fry ‘a buffoon’. N.B. Most extant studies have focussed on the highland clearances. Tom Devine and others have argued, convincingly, in more recent years that significant clearances occurred in lowland Scotland. See Aitchison, P and Cassell, A. (2003) The Lowland Clearances: Scotland’s Silent Revolution Birlinn: Edinburgh, Devine, T. (2018) The Scottish Clearances: A History of the Dispossessed, 1600-1900 London: Allen Lane.

13 There are plenty of examples of Scots, whether admirable or not, who really did start businesses from near nothing – for example, William Lithgow the shipbuilder, Robert Fleming, the Dundee clerk who started an international investment bank, Brian Souter and his sister Ann Gloag from Perth who set up Stagecoach and, of course, the example most often cited, Andrew Carnegie who made his fortune in American steel.

14 An example of the latter would be James Stevens the butler in Kazuo Ishiguro’s 1989 Booker prize-winning novel The Remains of the Day, notably played by Anthony Hopkins in the acclaimed Merchant/Ivory film of the same name (1993).

15 The Earl was killed leading 60 men of his then regiment, the 12th Lancers, to try to take Boer guns at the battle of Diamond Hill (or Donkerhoek). This battle took place on the 11th and 12th of June and resulted in around 60 killed and 100 wounded. Previously he had taken part in colonial wars in Afghanistan (1878-9) and Sudan (1884-5).

16 I was told recently that the owner of Airlie estates was considering applying for charitable status in order to gain funding to maintain and upgrade the monument – which is a bit frayed at the edges. If true, this would be yet another example of the landed seeking benefits to improve their property.

17 The de Maule’s were another of the 11th century Norman French cohort. Carnoustie has, since 1992, been twinned with Maule, a small town to the north west of Paris, France from whence came the original de Maule family.

18 Compare with rented accommodation in continental Europe.

19 Bol, D. (2019) ‘Dozens of rogue Airbnb-style flats in Edinburgh hit with warning letters.’ The Scotsman 15th May 2019